Venice in three excuses

I

I come to Venice with an excuse. It seems important.

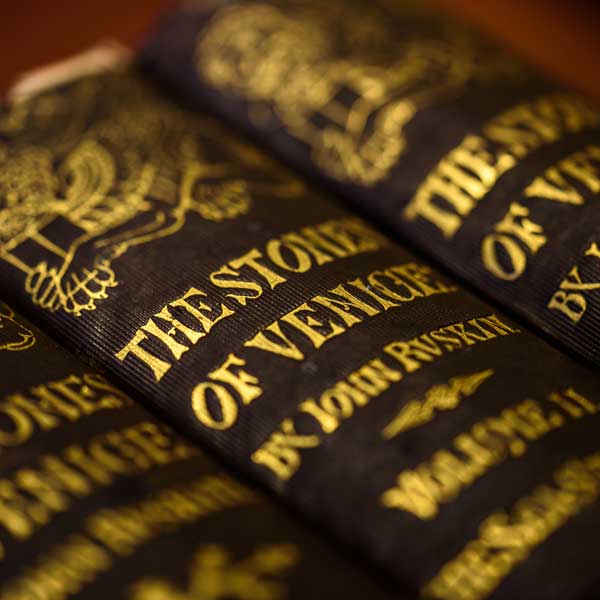

I’m seventeen and apprenticed as a potter and my first excuse is to follow in the steps of John Ruskin who I am besotted by. His drawings and watercolours of the grandiose dereliction here in Venice, his threnody for lost belief, for lives lived with purpose talk directly to my fervent desire to become a craftsman, to talk directly to the past. I come with my stoical younger brother on the train from London and I insist on using The Stones of Venice as a guidebook. We get very cold as pilgrims should. Almost forty years later when I think of Ruskin I feel a deep Venetian cold.

II

My second excuse is Marco Polo. My life as a potter has centered on porcelain. It is more than a beautiful, seductive white clay. It is a material that tells stories, stories that unfold and interweave as delicately as any Gothic tracery. And in his travels Marco Polo reaches “a city called Tinju.” Here, “they make bowls of porcelain, large and small, of incomparable beauty. They are made nowhere else except in this city, and from here they are exported all over the world.” (Marco Polo, The Travels, Penguin UK 1974).

This is the first mention of porcelain in the West. It describes porcelain as a material that is beautiful beyond comparison, that is complex to create, that these vessels are innumerable. Porcelain demands attention and dedication. And Marco Polo shrugs, “What need to make a long story out of it?”

He came back with a small grey-green jar made from this hard, clear white clay unlike anything seen before. And it is in Venice that object and name come together and start this long history of desire for porcelain. The name of this grandest of commodities, this white gold, comes from eye-stretching Venetian slang. This how words happen.

I have decided, after decades of making porcelain vessels, sitting crouched over my potter’s wheel with the rhythm of picking up one ball of porcelain after another to create one volume and then the next, that I need to understand where my obsession comes from. I need to go back to the source. Knowing that Marco Polo’s jar is somewhere in the Basilica in Venice, it is imperative that I go and find it.

I borrow Matthew, my middle child, and decide to chance it.

We get to the far left corner of the Basilica, the knots and eddies of tourists, handbag salesmen scanning for police, and through the glass doors of the Patriarchate where I make my pitch to a Monsignor who is charmed and delighted and suggests tonight, when everything is closed? And as they are closing up we are taken by the man with the key along a marble corridor in the Patriarchate past the terrible portraits of cardinals and into the shadows, the rolling swell of the marble pavements of the Basilica with its dull glimmerings, the red flare of the sanctuary lamps, into the Treasury.

It is small and high vaulted. Rock crystal and chalcedony, agates, chalices. A reliquary of the True Cross with gems set emphatically as a child’s kisses. This is Byzantium, this Treasury, Christ ascendant, conquering, one object after another from somewhere far away transfigured through Venetian skill.

And my jar is there, at the back of a cabinet between a pair of incense holders and a mosaic icon of Christ. It is a white promise. It is five inches tall, I guess, far less than a hand span, a frieze of foliage, four small loops below the neck to hold a lid, five indentations for thumb and fingers. An object for a hand’s memory. I can’t pick it up. The clay looks grey and rough and a bit raggedy where it has been trimmed roughly. It has come a very, very long way.

We peer at it for ten minutes until the man with the key starts tapping his foot. The Treasury is locked up. The Basilica is empty.

It is a start. Venice is a good place to start journeys as well as end them. Matthew is pleased I’m pleased and we go and celebrate at Florians in the Piazza with hot chocolate and macaroons like proper tourists.

III

My third excuse begins in the Campo di Ghetto Nuovo. It is early in the morning and I am nursing my cup of coffee and the first of my bag of dolci ebraici veneziani. They are rather too good. It is quiet but I can just make out the sound of the water from the fountain as the children clatter on their way to school and the metal shutters go up across the canal.

Being in this place, returning to this place repeatedly, is becoming another obsession. The history is undisputed: it was decreed in 1516 that all the Jews of Venice were to leave their homes and live ‘united’ in the square of houses near San Girolamo. There were to be two gates, opened in the morning and closed in the evening: the Christian guards were to be paid for by the Jews. New walls were to be built and the canals around this new area were to be patrolled by boats. It was to be a place of safety – Venetians were to be safe from the contamination of the Jews. By extension Jews were to be safe from the pogroms.

I make pots – hence Marco Polo. I am a writer – hence language. And sitting here I think of the great sweep of languages of this place, the mingling of high and low argot and slang, of the dialects of the Armenians, Germans, Flemish, Persian Ottoman, Spanish and Portuguese Jews alongside Italians. This is a place of constant translation, a testing ground for comprehension and nuance, noisy with learning, education, debate, poetry and music, liturgy and exegesis.

Everything is plural here, one history reaching out to another, a palimpsest of voices. When I had the idea of threading an exhibition through some of these spaces, I thought of how the psalms work as songs of exile from the city, the ever-present absence of Jerusalem. The psalms are songs that move between the singular and the plural, the solitary voice and the tribal, anger and despair and lament to joy. I was given Rilke’s story of an elderly man in the Venice Ghetto and his yearning to move higher and higher: “Finally, they were living at such a height that when stepped out of the narrow confines of their apartment onto the flat roof, their heads already reached a level where a new county began, of whose customs the old man spoke in dark words, as though half caught up in the raptures of a psalm.” (Rainer Maria Rilke, A Scene from the Venetian Ghetto).

IV

Who needs an excuse to come to Venice? Perhaps this searching out of problems is a kind of mapping out of possibilities, other futures and other histories. I’ve left my Ruskin at home and now carry Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities with me. My final excuse is that this city is the city of translation, of a plurality of voices, of language in flux. And of printing. I start to study the beautiful early editions of the Talmud printed here by Daniel Bomberg in the sixteenth century and sent out across the world and when I see how he kept text and commentary on text alive on a single page, I start to think that I need to create a new library for this city of libraries. It is to be a library of exile of two thousand books written by those who have been forced to flee their own country or exiled within it can.

The external wall of the library will be covered in porcelain, painted in liquid form over sheets of gold into which I’ve written a new text – a listing of the lost and erased libraries of the world. As I wrote it I realised that this writing of one text on top of another, one history smudging the one beneath, was as close as I was ever going to get to Venice.

BIO

Edmund de Waal (Nottingham, 10 September 1964) is a famous ceramist and author of The Hare with Amber Eyes (Vintage 2011) and The White Road. A Journey into Obsession (Vintage 2016). On the occasion of the Art Biennale, de Waal is present in Venice with an exhibition that includes two installations on the theme of exile: the first at the Museo Ebraico and the second within the Great Hall of the Ateneo Veneto.